The Visit: A Short Story by Lisa Vega

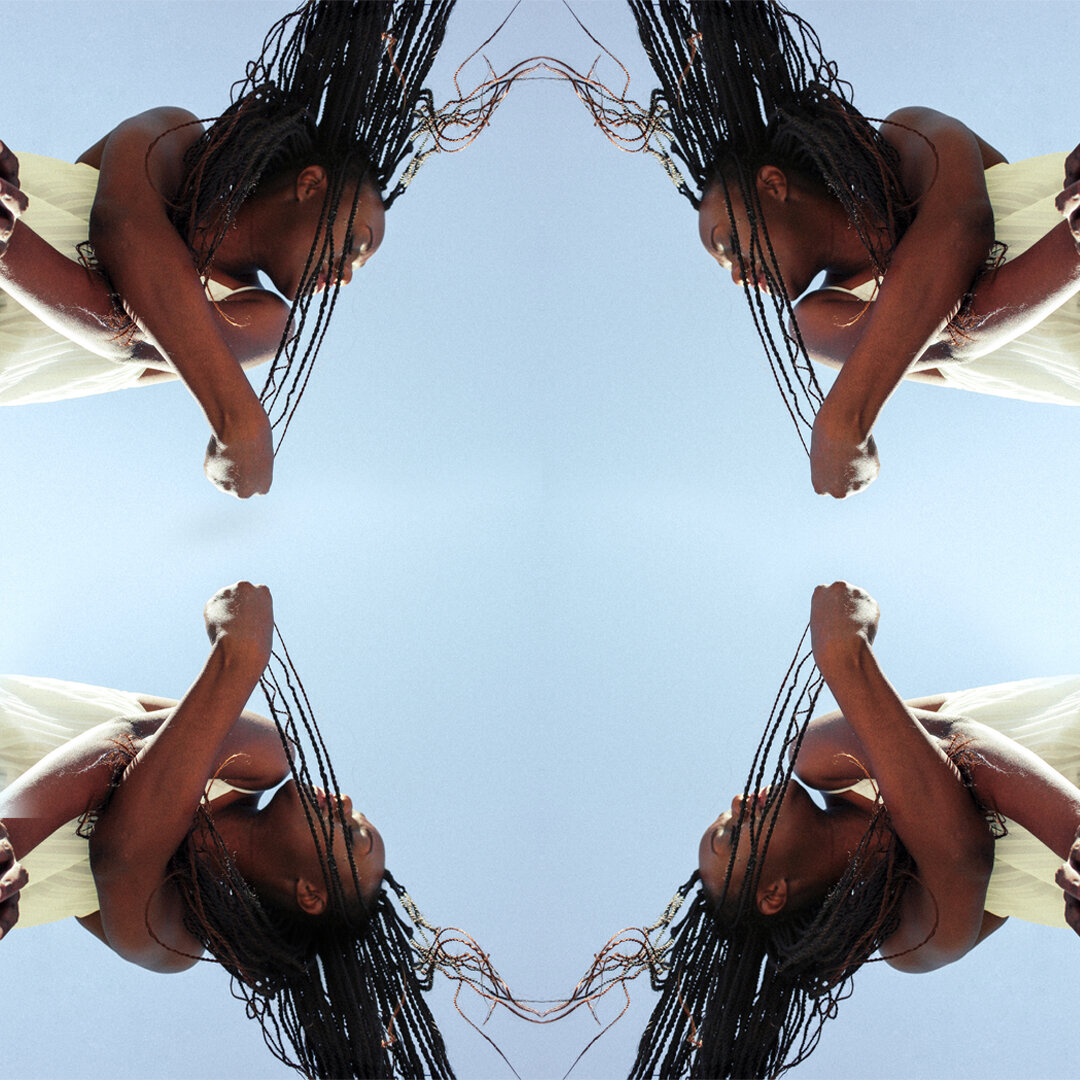

Art Direction and Photograph by: Catie Menke. Model: Gabriella Noelle.

Short Story Written by: Lisa Vega

Creative Direction by: Catie Menke

The Visit by Lisa Vega

A young woman sits upon a bullet train from Tokyo to Odawara, staring through the window at a gray-beige sea of apartment buildings. There are no words to the song she listens to, but the sad melody accompanies the view like a soundtrack. A gentle voice announces the next stop, and the young woman, heart pounding, listens intently for hers.

The ride one way is an hour-and-4,000-yen commitment. It’s expensive in other ways too, and for that all the more important. She steadies her breathing as she steps off the train onto the platform. A double set of stairs to her right leads into the station. It’s humid even inside, and her coarse black hair sticks to her forehead as she gazes into gift shops and cafés.

She tries to remember her visit to Grand Central Terminal when she was a child. There’d been a grandeur about the place, a sense of decoration for its own sake. In Japan, the young woman marvels at utilitarian things: buildings stacked as high and narrow as practicality will allow, sharp angles and neutral hues, the brandlessness of her newly purchased gray skirt and white sneakers.

According to the directions on her phone, the young woman must take a bus. That’s as far as technology will get her, unfortunately. Trekking to the east entrance of the station, she arrives at a massive lot, a row of shuttles and a chart listing the stops in Japanese. She resigns herself to asking for help.

“Sumimasen,” the young woman calls sheepishly to a bus driver. She hands him a slip of paper with the address on it and speaks into her phone. “Which bus should I take?”

“Dono basu ni noreba īdesu ka?” the phone repeats. The driver leans forward to listen, then points to a large purple bus on the other side of the lot.

A man watches the evening news as a typhoon hits parts of Japan. A text from his daughter lights up the screen of his phone. He peers down at the preview without lifting it off the coffee table: I hope your mom is okay. His daughter has never met her grandmother, though that’s hardly his fault.

He glances from his phone to Mr. Saeki’s business card thrown unlovingly onto the kitchen counter. A miserable souvenir from his most recent and decidedly final attempt to visit two years ago. Now, like many other scraps around his apartment—old receipts, grocery lists, memos scribbled on napkins—it collects dust.

Mr. Saeki was a young gentleman in his 30s, who had glasses and a nervous laugh. They’d spoken before over the phone but met in-person for the first time in a hotel lobby. To remember the day is to resurrect emotions he’d rather leave buried: the sting of pity from a stranger; the empty feeling as he sat alone, staring at the space left on the couch where his mother should have been; the nagging voice that reminded him he should have known better.

From what little the two could understand of each other, Saeki might have been the designated agent in his mother’s power of attorney, or at least a close confidante.

“What do you mean?” The man had asked. “I came all this way.”

“Many apologies,” Saeki repeated, deepening his bow.

He was told repeatedly that she didn’t feel well enough to visit and wasn’t taking visitors. The man is above begging. He’d accepted a slip of paper with her direct line and Mr. Saeki’s business card but hasn’t called either of them since.

Another text overtakes the first in the notification window: How are you doing? He reaches down and taps the power button to darken the screen.

The man is tired. If he has time, perhaps he’ll shoot an email to Mr. Saeki in the morning.

A mother eats the lunch brought to her room by the nurse. The spoon wobbles in her trembling hand, but for now, this is something she can do without help. Her head is clear today; that’s good. Other days she’s not so lucky, only basking in brief moments as they break through the fog.

The mother likes to think herself pragmatic, if a bit stubborn. She began to get her affairs in order the moment she realized her mind was slipping away from her, but she insisted on her independence for as long as she could.

One day, she fell. If not for her young neighbor, a man who had by then become a dear friend, she would have remained on the floor of her bare Tokyo apartment, wondering how her life had carried her there. She could no longer stall the inevitable. After leaving one hospital, she admitted herself into another.

When the nurse returns, she has with her a small tray holding two pills. The mother accepts one, taking it with water, and then the other. She welcomes the warm cotton fuzziness they bring. The nurse wheels her over to the window, where she can admire the swaying trees.

On days with nice weather, one of the staff will wheel her out to the courtyard or sometimes walk her around the grounds. Today’s a little too hot—better for the window and some knitting, or one of her old movies.

The young woman steps off the bus in wonder. If Tokyo had been a labyrinth of steel and glass and synthetic light as far as the eye could see, Odawara is a worn, white paper city folded out of a dense jungle. The sky is larger here, and the feeling she’s lost inside something massive doesn’t stalk her like a shadow. Cicadas’ songs fill her ears. She crosses a bridge, letting a hot breeze blow the matted hair from her neck.

The phone directions fall apart around here without translation. Luckily, there’s nowhere to go except through a small tunnel beneath the train tracks. She emerges to a neighborhood of cramped streets and buildings in all shapes and colors. Examining each, she can’t tell business from residence. She looks down at the address in her hand. Squints at house numbers on her left and right. Nothing is in order.

But where her head is uncertain, her feet are determined. She walks and sweats and walks. She approaches an old man for directions, and he points up and to the west. They’re at the base of a hill. The young woman’s destination, she can only assume, is at the top.

The man pays no mind to Mr. Saeki’s business card in the morning. He combs his hair and puts on a clean uniform and comfortable shoes and leaves. He stops at a drive-thru for breakfast. He pays no mind to the voice in his head either, the one that tells him what he ought to do. He is a man with a busy day and has no time for ruminating.

He’s clocking into work when his phone vibrates on his hip. His daughter again. He burns with minor annoyance at her persistence. Why she can’t help but buzz around his ear—and this early in the morning—is beyond him. The workload is heavy today, and he’d like to get a head start. He is a man of responsibility, after all, and a phone call can wait until his lunch break.

When noon rolls around, he remembers he needs to make a return. He reasons he may not get another chance before his 30-day window closes, and there’s no time like the present. He has just enough time to make it home and to the store and back. A phone call would certainly slow him down, and the weekend is more appropriate for leisurely chats anyway.

It’s dark when the man leaves work. His shoulders slump and his legs are sore, but he’s got enough juice left in him to grab some groceries. A few frozen dinners, a six-pack of diet cola, a fresh bottle of hand soap. He’s a simple man with very few needs, and that there is the key. He’s learned never to expect too much.

The business card mocks him on his way in. The voice mocks him too, and he powers on the TV to drown it out. There’s pizza in the fridge from yesterday—or maybe the day before. He brings a cold slice and a room-temp cola with him to the couch where the cushions are plush, the leather cool. He happily descends into them.

With the typhoon still in the headlines, he decides to watch the game instead.

The man is tired—too tired to think about his mother’s safety in a country out of his reach. Or to broach the subject with his daughter, who wants so badly to poke at all the places where it hurts.

He’ll be too tired to pull himself together if he happens to fall apart, so he must be careful of sharp corners and sudden drops.

“I’d like you to help me with something, if you don’t mind,” the mother tells her neighbor, who has stopped in to bring her weekly groceries.

“Of course, Matsuo-san,” Yuuto replies.

“I need you to meet my son at his hotel,” the mother says solemnly, “and tell him I cannot see him.”

The young man looks shocked for a moment. He knows of their estrangement and has spent considerable time to help her arrange for this meeting. Though she never speaks of why the two have grown apart, Yuuto has thus far been too polite to pry.

“If I may, Matsuo-san…” He looks uncomfortable. Boldness doesn’t suit him. “Why do you not wish to see him?”

Oh, but she does. Her bones ache and scream with it. She dreams of the moment nightly and torments herself in the daylight with fading memories of his face.

But it’s been far too long. With each passing day, the possibility seems less possible, and the notion of a real, tangible son seems more fantastical. Would she not shatter now at the sight of him? Would she not be crushed under the weight of so many wasted years?

She’s frailer than she’s ever been. She hates seeing her own small, hunched shoulders in the mirror and can stand far less to be seen this way by others.

“I’m not feeling well enough to visit,” she says finally, “or receive visitors.” She turns from him to hide her face, though there’s nothing to see there. She is a statue, cold and crumbling. She cannot, after all this time, be changed.

The young woman doesn’t enter her father’s apartment right away. Just swings the door open and peers in from a faded welcome mat. It smells vaguely of sweat. Aside from the clutter and dust, it looks well taken care of. The floors are swept, the furniture like new. Taking a deep breath, she hefts a stack of flattened boxes into the entryway. It’ll be some work to do on her own, but there is no one else to do it.

In his final years, her father went radio silent. She left that part out of the eulogy, sticking to recounting memories of a big, bubbly goof who couldn’t take a thing seriously. Or didn’t ever want to. Thinking on it now, perhaps that new darkened version of him was always there, waiting for its turn.

“You replaced one fortress with another,” she says aloud to the air. She wants to believe he’s there, floating in it. She wants him to know that she knows and that she understands and that she’s not mad. This is the only chance he would give her to say so.

As she packs up his things into boxes, she finds a worn business card in the kitchen. The writing is Japanese, but she flips it over to find an English alphabet translation. Saeki Yuuto. She knows him from ancient conversations with her father. She understands the opportunity, and she resolves to take it.

She doesn’t blame him. To start a new life in a foreign country would be far too difficult at his age. It would be better for him to remain in America, finish school and live out a life in the place he knows. She tries to see it that way and not as some new injury, which is how it feels. He’s choosing his father over me. I, who have loved them both so deeply it hurts, am cast out.

“I understand,” she says plainly. She was never one for too many words or feelings. Even as the ground gives beneath her, she dares not lose footing.

The mother would stay if she could, undignified as it is. She would cling desperately to her child, though he wouldn’t do so for her. But she has no such choice. To survive, she too must live out a life in the place she knows.

As soon as the divorce is final, the mother books a flight back to Tokyo to stay with her parents. No tears are shed at the airport as she says her goodbyes to her son. Her face is stone, his fire. He crosses his arms over his chest and will not look at her. So you too are betrayed, she thinks.

She carries out each subsequent day minimally, resolute. She’s courted by a journalist, an old friend of the family, and her mother encourages her to see where it goes. He’s nice, with a handsome smile that crinkles the corners of his eyes. The time of cherry blossoms comes and goes, and even as the onset of summer warms and dampens the air, her world is colder.

Of all the things I expected, the young woman thinks, panting, a hike was not one of them. She shuffles along an inclined road, passing turns she’s not sure she shouldn’t take. The air is feels heavy with moisture. It weighs her down too, sinking into the fibers of her sheer cotton blouse. She fans the hem up and down, but it doesn’t help.

Her anger builds as the hill grows steeper, the buildings more ambiguous. To have come this far for nothing… Years ago, she remembers, her father crossed the ocean. He returned but not really. He got lost looking for something he couldn’t find. The young woman wonders if he felt as she does now—if he wrapped his arms around himself, as she does, if only to hold all the pieces in place.

She doesn’t hear the small white car approach until it’s pulled up beside her. The driver is the old man who gave her directions. He gestures to the passenger seat, then up the hill, and the young woman doesn’t know what to do but cry and laugh and bow repeatedly. Thank you, she can’t manage to say. She climbs into the car, and they drive up the road together.

The nursing home resembles a large apartment building, with rooms and balconies stacked several floors high. The young woman recalls the view from the train with its sad song. This feels innately different—a quiet sanctuary balanced delicately along the side of the hill and shrouded in greenery.

As she exits the car, thanking the old man for his kindness, she hums happily to herself a song about starting over.

The nurse enters the mother’s room once more. “Good afternoon, Matsuo-san,” she says, wheeling her away from the window. “Your visitor is here.”

Yes, she has a visitor today. It is another detail that has escaped from her in the fog, but it’s back now and she’s glad for it. Though she doesn’t recall who the person is who has come to see her, she feels strongly that they’re family. Family. The word sounds strange these days. Everyone she once called family is gone: her mother and father, both late husbands, a son. Her memory of them has become liquid and dreamlike, as distant memories tend to do.

Perhaps it’s the pills, but this too feels like a dream, one she doesn’t deserve. Bitter and sweet like barley tea with honey.

The nurse arranges her with her blanket by a small table in the center of the room. “I’ll go get her and bring the two of you some tea,” she says.

She returns beside a young lady in a white blouse and gray skirt. Tall, with darker skin than most here. Her hair is coarse and familiar. The sight of her is painful in a way the mother can’t put words to. She feels she’s had this meeting before, though that can’t be the case.

The young woman speaks English into a phone, and the phone repeats the words back in the mother’s own tongue. The sound of them fills her heart to the brim and over.

“Kon’nichiwa, obāsan. Jikan ga kakatte gomen’nasai.”