Maori Time: What I Learned from Escaping Strict Scheduling and Flowing with the Spontaneous Events of Life

Image of Jeni Fjelstad.

Copy by: Jeni Fjelstad

Creative Direction: Catie Menke

Americans often take time for granted. Seven a.m. breakfast, noon lunch and 6 p.m. dinner; we live by clockwork, and I would say it brings most of us comfort.

However, not all cultures view time so strictly.

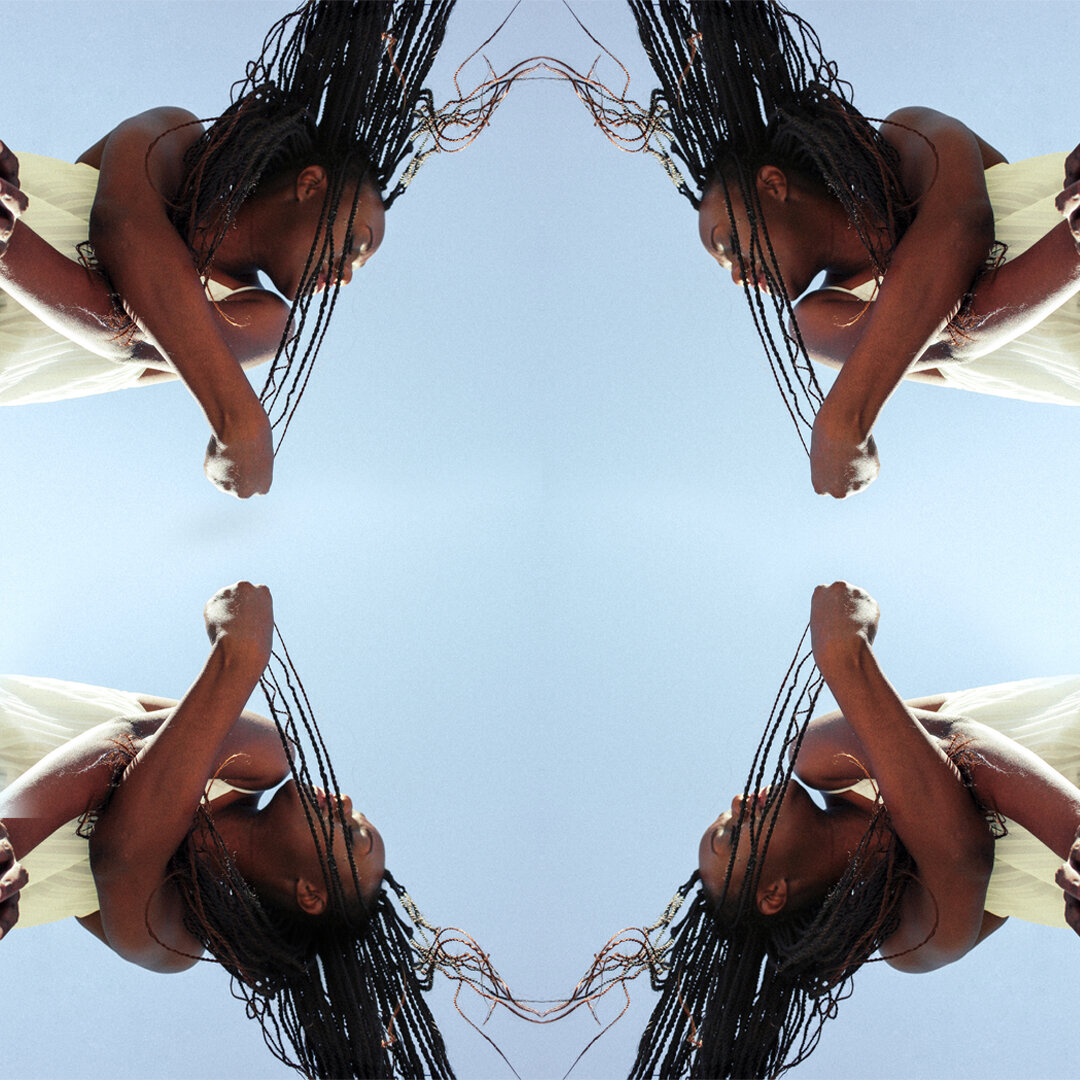

No wind, no clouds, the sun beats down through the funnel mountains on each side of the Whanganui river. Three six-person wakas (canoes) and three two-person wakas paddle in synchronization with the calls “hoea,” or paddle, from our guides, Ash, Mama, and Paré.

Photograph by: Jeni Fjelstad.

Half-way around the world in New Zealand, a community of native people of the island nation, the Maori, graciously hosted our class trip for two days of immersive learning, and not even the professors knew what to expect.

That night, all 21 of us stayed mattress to mattress in a marae, a sacred cultural place of gathering, remembrance, and hosting guests. The group waited impatiently for dinner as 6 p.m. passed, then 7 p.m. The most logistical members of the group started asking questions: when would we eat?

But that was against the rules of immersion in Maori-time. Ash would answer no logistical questions.

As for me, I like to take my sweet time getting from one task to the next. My friends call it “Jeni time,” and much like Maori time, I find comfort in escaping strict scheduling and flowing with more spontaneous events.

So, instead of letting us know when dinner was, Ash filled our time with discussion of culture and ancestry.

We did as he instructed, reached forward, and adjusted our hands to the side, where they were no longer visible in our periphery.

“The past is in front of us, and the future is behind us,” Ash explained. “We know nothing that will happen in the future, but we have the people and experiences of the past to guide us.”

The contrast with Western concepts like “leave the past behind you” and “forward-thinking,” made my jaw drop. Professors and students alike were astonished.

Even the structure of time was no longer certain.

When our beef mince and noodles were finally prepared, it was about 9 p.m. —not that it mattered.

Although Ash had previously declared teachings finished for the day, it was a perfect night to gaze at the stars of the Southern hemisphere. In a Maori worldview, the correct time for learning is right before sleeping because it allows the subconscious to open and absorb information.

Ash’s red laser pointer seemed to poke each star as he connected the dots for us. Blatantly clear was the waka sailing through the sky with Orion’s belt as its seat, and once again, time slipped away.

Taking mercy on my logistical friends, Ash told us breakfast would be at 9 a.m. the next day. But we were in for yet another surprise.

The intense summer sun was on the rise, and, following the signs of nature, it was Maori time to wake up and begin another day’s journey. We awoke at 7 a.m. to Ash strumming the Beatles’ “Let it Be” on his trusty acoustic guitar.

In my opinion, it was a lovely way to wake up, but disrupting the sleep schedule of nineteen teenagers, who have just spent a day canoeing down a river in a foreign country, did not meet with such a warm reception.

Still, back to the river we went, swapping out pairs of students into different canoes.

The guides laughed, sang, and teased, accepting each South Dakotan into their whanau, or family.

After banking the canoes and hiking up a steep hill, we began to prepare our meal atop a silver fern tablecloth. Maori hospitality centers on help from guests, lending control as a gift of comfort. As helpful Midwestern people, we were happy to chop tomatoes, slice avocado and arrange bags of chips. Noon? 2 p.m.?

Many more moments passed, unmarked by time and only accounted for by memory, and when it was our time to return to western culture in the capital city, Wellington, it took us days to adjust.

Our worldview, our entire concept of time, our obsessive tendency to calendar each moment into a strict schedule— all three were completely discredited in less than 48 hours.

Now, when I dawdle a bit from task to task, my friends from the trip know I simply run on Maori time. So, as I walk slowly backward through life, I can be sure to take in all the signs, appreciate sweet moments, and acknowledge all the moments that have brought me to my place.